Page 118 - Profile's Unit Trusts and Collective Investments 2021 issue 2

P. 118

CHAPTER 6

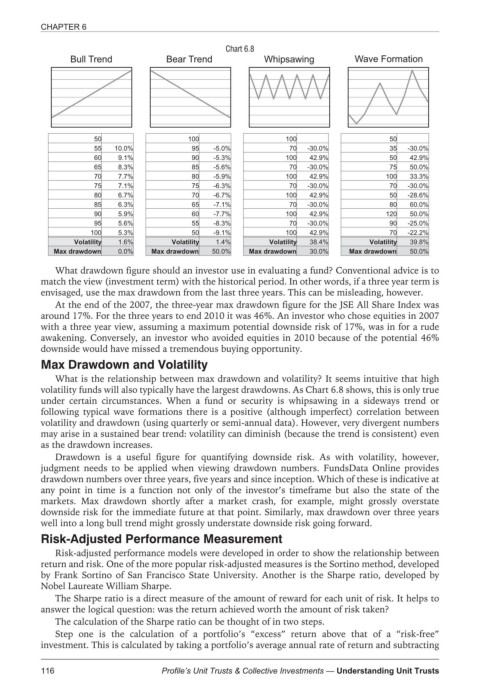

Chart 6.8

Bull Trend Bear Trend Whipsawing Wave Formation

50 100 100 50

55 10.0% 95 -5.0% 70 -30.0% 35 -30.0%

60 9.1% 90 -5.3% 100 42.9% 50 42.9%

65 8.3% 85 -5.6% 70 -30.0% 75 50.0%

70 7.7% 80 -5.9% 100 42.9% 100 33.3%

75 7.1% 75 -6.3% 70 -30.0% 70 -30.0%

80 6.7% 70 -6.7% 100 42.9% 50 -28.6%

85 6.3% 65 -7.1% 70 -30.0% 80 60.0%

90 5.9% 60 -7.7% 100 42.9% 120 50.0%

95 5.6% 55 -8.3% 70 -30.0% 90 -25.0%

100 5.3% 50 -9.1% 100 42.9% 70 -22.2%

1.6% 1.4% 38.4% 39.8%

Volatility Volatility Volatility Volatility

0.0% 50.0% 30.0% 50.0%

Max drawdown Max drawdown Max drawdown Max drawdown

What drawdown figure should an investor use in evaluating a fund? Conventional advice is to

match the view (investment term) with the historical period. In other words, if a three year term is

envisaged, use the max drawdown from the last three years. This can be misleading, however.

At the end of the 2007, the three-year max drawdown figure for the JSE All Share Index was

around 17%. For the three years to end 2010 it was 46%. An investor who chose equities in 2007

with a three year view, assuming a maximum potential downside risk of 17%, was in for a rude

awakening. Conversely, an investor who avoided equities in 2010 because of the potential 46%

downside would have missed a tremendous buying opportunity.

Max Drawdown and Volatility

What is the relationship between max drawdown and volatility? It seems intuitive that high

volatility funds will also typically have the largest drawdowns. As Chart 6.8 shows, this is only true

under certain circumstances. When a fund or security is whipsawing in a sideways trend or

following typical wave formations there is a positive (although imperfect) correlation between

volatility and drawdown (using quarterly or semi-annual data). However, very divergent numbers

may arise in a sustained bear trend: volatility can diminish (because the trend is consistent) even

as the drawdown increases.

Drawdown is a useful figure for quantifying downside risk. As with volatility, however,

judgment needs to be applied when viewing drawdown numbers. FundsData Online provides

drawdown numbers over three years, five years and since inception. Which of these is indicative at

any point in time is a function not only of the investor’s timeframe but also the state of the

markets. Max drawdown shortly after a market crash, for example, might grossly overstate

downside risk for the immediate future at that point. Similarly, max drawdown over three years

well into a long bull trend might grossly understate downside risk going forward.

Risk-Adjusted Performance Measurement

Risk-adjusted performance models were developed in order to show the relationship between

return and risk. One of the more popular risk-adjusted measures is the Sortino method, developed

by Frank Sortino of San Francisco State University. Another is the Sharpe ratio, developed by

Nobel Laureate William Sharpe.

The Sharpe ratio is a direct measure of the amount of reward for each unit of risk. It helps to

answer the logical question: was the return achieved worth the amount of risk taken?

The calculation of the Sharpe ratio can be thought of in two steps.

Step one is the calculation of a portfolio’s “excess” return above that of a “risk-free”

investment. This is calculated by taking a portfolio’s average annual rate of return and subtracting

116 Profile’s Unit Trusts & Collective Investments — Understanding Unit Trusts