Page 116 - Profile's Unit Trusts and Collective Investments 2021 issue 2

P. 116

CHAPTER 6

Quantitative vs Qualitative

Most of the methods for evaluating risk mentioned in this section are quantitative – that is, they are

calculations based on quantifiable fund data. Quantitative analysis is essentially the mathematical

and statistical interrogation of data in order to measure performance, risk and other factors.

Qualitative analysis, by contrast, depends on the subjective judgment of industry experts and

concerns itself with factors that cannot easily be quantified, such as management expertise, investment flair, and

economic cycles. Traders, researcher and fund managers who rely heavily on quantitative analysis are often

referred to as “quants”, although the term is also used to describe the metrics of a fund or other investment

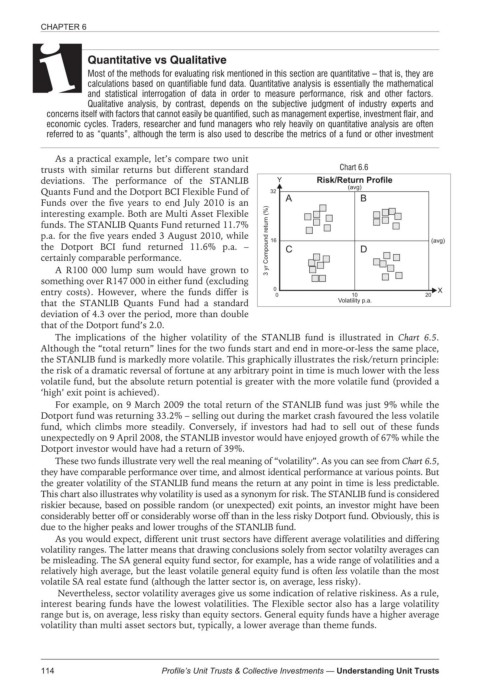

As a practical example, let’s compare two unit

trusts with similar returns but different standard Chart 6.6

deviations. The performance of the STANLIB Y Risk/Return Profile

(avg)

Quants Fund and the Dotport BCI Flexible Fund of 32

Funds over the five years to end July 2010 is an A B

interesting example. Both are Multi Asset Flexible

funds. The STANLIB Quants Fund returned 11.7%

p.a. for the five years ended 3 August 2010, while 3 yr Compound return (%) 16 (avg)

the Dotport BCI fund returned 11.6% p.a. – C D

certainly comparable performance.

A R100 000 lump sum would have grown to

something over R147 000 in either fund (excluding

entry costs). However, where the funds differ is 0 0 10 20 X

that the STANLIB Quants Fund had a standard Volatility p.a.

deviation of 4.3 over the period, more than double

that of the Dotport fund’s 2.0.

The implications of the higher volatility of the STANLIB fund is illustrated in Chart 6.5.

Although the “total return” lines for the two funds start and end in more-or-less the same place,

the STANLIB fund is markedly more volatile. This graphically illustrates the risk/return principle:

the risk of a dramatic reversal of fortune at any arbitrary point in time is much lower with the less

volatile fund, but the absolute return potential is greater with the more volatile fund (provided a

‘high’ exit point is achieved).

For example, on 9 March 2009 the total return of the STANLIB fund was just 9% while the

Dotport fund was returning 33.2% – selling out during the market crash favoured the less volatile

fund, which climbs more steadily. Conversely, if investors had had to sell out of these funds

unexpectedly on 9 April 2008, the STANLIB investor would have enjoyed growth of 67% while the

Dotport investor would have had a return of 39%.

These two funds illustrate very well the real meaning of “volatility”. As you can see from Chart 6.5,

they have comparable performance over time, and almost identical performance at various points. But

the greater volatility of the STANLIB fund means the return at any point in time is less predictable.

This chart also illustrates why volatility is used as a synonym for risk. The STANLIB fund is considered

riskier because, based on possible random (or unexpected) exit points, an investor might have been

considerably better off or considerably worse off than in the less risky Dotport fund. Obviously, this is

due to the higher peaks and lower troughs of the STANLIB fund.

As you would expect, different unit trust sectors have different average volatilities and differing

volatility ranges. The latter means that drawing conclusions solely from sector volatilty averages can

be misleading. The SA general equity fund sector, for example, has a wide range of volatilities and a

relatively high average, but the least volatile general equity fund is often less volatile than the most

volatile SA real estate fund (although the latter sector is, on average, less risky).

Nevertheless, sector volatility averages give us some indication of relative riskiness. As a rule,

interest bearing funds have the lowest volatilities. The Flexible sector also has a large volatility

range but is, on average, less risky than equity sectors. General equity funds have a higher average

volatility than multi asset sectors but, typically, a lower average than theme funds.

114 Profile’s Unit Trusts & Collective Investments — Understanding Unit Trusts