Page 117 - Profile's Unit Trusts and Collective Investments 2021 issue 2

P. 117

Investment Risk

Chart 6.7

100

97

95

92

90 91

85 84

83

80

79 79

78 77

76 76

75

72 72 72

70 69

68

67

65 64

63 63

61

60

58

56

55

52

50

J F M A M J J A S O N D J F M A M J J A S O N D

In short, the greater the equity component – and the more narrowly focussed that equity

component – the greater the volatility. While a useful rule of thumb, it must be remembered that

there are many exceptions to this principle.

Scatter plots are often used to compare the relative risk and return of different funds (see Chart

6.6). The lines dividing the quadrants represent the average risk and the average return of funds

represented in the graph. Return is plotted on the y-axis and risk, or volatility, on the x-axis. Ideally,

a fund should be in the top left quadrant (A), giving above-average returns at below average risk.

Funds that have above average returns but are high risk fall into the top right quadrant (B). Funds

with below average returns but low risk fall into the bottomleftquadrant(C),and quadrant (D), the

worst place to be, shows funds with higher than average risk and lower than average returns.

As with all historical analysis, past performance is not always a good predictor of future

performance (ie, today’s low-risk high-return star may be tomorrow’s high-risk low-return failure).

Also, looking at the scatter graph for a single fund in isolation can be misleading (and for this reason,

an attempt is made on the risk/return graphs shown for certain funds in the fact sheets in section

two of this Handbook to plot scatter charts on identical scales for the same periods.) Nevertheless, in

the same way that historical performance figures give us a measure of a fund manager’s ability to

generate consistent returns, volatility gives us a measure of the risk associated with a fund.

Max Drawdown

Maximum drawdown (often shortened to max DD or MDD) is a risk measure that expresses

maximum loss on a peak to trough basis. A related figure, drawdown duration, is the longest time

an investment took to regain a former peak.

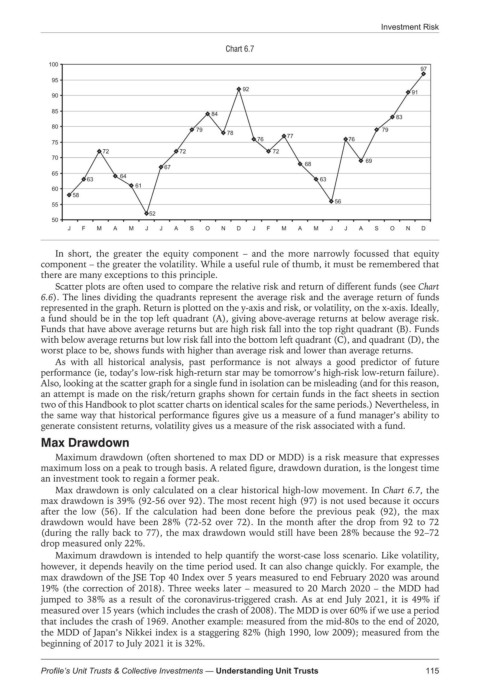

Max drawdown is only calculated on a clear historical high-low movement. In Chart 6.7, the

max drawdown is 39% (92-56 over 92). The most recent high (97) is not used because it occurs

after the low (56). If the calculation had been done before the previous peak (92), the max

drawdown would have been 28% (72-52 over 72). In the month after the drop from 92 to 72

(during the rally back to 77), the max drawdown would still have been 28% because the 92–72

drop measured only 22%.

Maximum drawdown is intended to help quantify the worst-case loss scenario. Like volatility,

however, it depends heavily on the time period used. It can also change quickly. For example, the

max drawdown of the JSE Top 40 Index over 5 years measured to end February 2020 was around

19% (the correction of 2018). Three weeks later – measured to 20 March 2020 – the MDD had

jumped to 38% as a result of the coronavirus-triggered crash. As at end July 2021, it is 49% if

measured over 15 years (which includes the crash of 2008). The MDD is over 60% if we use a period

that includes the crash of 1969. Another example: measured from the mid-80s to the end of 2020,

the MDD of Japan’s Nikkei index is a staggering 82% (high 1990, low 2009); measured from the

beginning of 2017 to July 2021 it is 32%.

115

Profile’s Unit Trusts & Collective Investments — Understanding Unit Trusts